Today, I got an invitation to contribute some chapters to an academic book. My research area is on offshore composite materials, called composite risers used in deepwater operations. However, I wanted to find out online discussions and opinions on academic journals and book chapters. This post includes the top views, opinions and contributions on this subject. Recent discussions about publishing academic and scientific research as book chapters in edited volumes instead of as articles in scholarly journals have suggested that book chapters do not get cited nearly as often as journal articles do.

By definition, a research article relates to findings or research investigations on certain specified topic or sub-topic, though a review article on certainly specified aspect provides the detailed account of that and provides information about what people (researchers) have done and have been doing on that specified topic. However, a book chapter that might be a review article, is presented for a book covering the detailed information with more descriptions inter-relating with the related aspects as well. Usually, a book chapter provides a continuity and relevant information linked with other chapters in the book as well.

Some other views include:

1. Book chapters are not papers.

2. They don’t get cited that much as journal articles but will get read.

3. Make sure your editorial is well-known (& also sells pdf versions /allow preprints in your web)

4. For early career researchers one/two book chapters can give you credit, but remember that you will be evaluated mainly on papers, so keep the ratio of books/papers low.

According to

Rene Tetzner(2005), "With citation reports and impact factors so central to a successful academic or scientific career these days, it is natural to wonder whether there is any point in contributing chapters to edited volumes. If citations are your main concern, then the answer may well be no, though accessibility is a key issue. If, for instance, the book is going to be released as an e-book that is searchable and accessible online, then your chapter will, at least theoretically, be as accessible as a journal article would be, provided you design your title, keywords and abstract (if one is included) in such a way that search engines will lead potential readers to your work. Yet many edited collections of essays are published only in print versions, at least for initial publication, and it is much less likely now than it was twenty years ago that a reader will find your chapter by chance while scanning a library shelf for writing on a given topic.

However, citations, as important as they may be, are usually not the only reason to publish research, and they certainly should not be. A book chapter often allows the author more scope and creativity to bring together ideas and theories and present them in original ways than a journal article does. An edited book of essays as a whole tends to gather together a variety of perspectives on a problem or phenomenon, producing a collection of considerable value for readers and especially for students and practitioners who are new to the subject or topic. In some instances, edited volumes will be used as instructional resources in courses, effectively becoming textbooks and influencing a new generation of scholars. Edited volumes will usually contain a few (or at least one) chapter by a well-established and well-cited academic or scientific author, and for contributors just beginning their careers, being published in close proximity to such scholars can be beneficial and suggest to employers and funding bodies that candidates have meaningful research connections.

There are, then, still some very good reasons to publish your research in edited volumes, and in the social sciences and humanities such collections remain common and books are still considered by some the gold standard of academic publication. If you are thinking of contributing a book chapter, however, do take a close look at the publisher, the volume’s editor(s) and the other contributors, as well as at the accessibility anticipated for the book, since these will be reliable indicators of the quality of the forthcoming volume, the ability of readers to find your work and the potential benefits for your research and career."

=====================================================================

Another researcher, Ahmed said: "It seems to me that, in Educational research at least, writing for peer-reviewed journals places different constraints on what we might write about, and how we might go about it. When sending something off for double-blind review by a journal, I notice that I’m more inclined to ‘play it safe’. It seems that one must be able to please any possible reader imaginable, as there is no control over who might be asked to make a decision about the article. This means the paper often ends up taking the form of a traditional ‘scientific’ paper reporting on empirical research, even so, I can’t seem to keep the results and discussion separate in qualitative research! It just doesn’t seem to make sense in the kind of writing I do.

In contrast, book chapters in edited collections seem to be places where one can take rather more risks. Book chapters allow more space for reflection on bigger ideas than journal articles, and a little more licence to be more adventurous in the approach to the topic. Perhaps this is partly because, again in Education research, the essay form is more common in book chapters than in journal articles. As part of an edited collection, these chapters don’t need to stand alone in the way that articles usually do, even in special issues; rather, they sit alongside other chapters exploring closely related issues. This often allows for some cross referencing between chapters, either by authors or the editors, so that each chapter doesn’t need to say absolutely everything on the topic, and the ideas can expand out beyond the individual chapter. In this situation, a quite distinctive, personally inflected contribution can be valued for the facet that it adds to the composite whole. It also seems that those reviewing the chapter, the editors and possibly other contributors to the collection, are likely to be a more empathetic readership in terms of their interests and concerns."

Thus, the simple comparison:

1. Article: Saunders (2007) states that articles are a vital literature source for any research. The articles are easily accessible. They are well covered by tertiary literature.

Saunders (2007) further states that articles in refereed academic journals are evaluated by academic peers prior to publication, to assess their quality and suitability. These are usually the most useful for research projects as they will contain detailed reports to relevant earlier research.

2. Books: According Saunders (2007) books and monographs are written for specific audience. The material in books is usually presented in a more ordered and accessible manner than journals, pulling together a wide range of topics. They are therefore particularly useful as introductory sources to help clarify your research question(s) and objectives or the research methods you intend to use.

==============================================================================

In an article by Cally Guerin (2014), titled "Journal article or book chapter?"; stated that: In the context of trying to find out more about theses by publication, I’ve been reflecting on where doctoral students might place their publications. What are the differences between the genres of journal articles and book chapters in edited collections? Are these differences significant, and if so, how? If we are to support doctoral candidates in their writing, it can be useful to have thought through the different opportunities these genres offer, especially if we are advising students to publish their research.

"It seems to me that, in Educational research at least, writing for peer-reviewed journals places different constraints on what we might write about, and how we might go about it. When sending something off for double-blind review by a journal, I notice that I’m more inclined to ‘play it safe’. It seems that one must be able to please any possible reader imaginable, as there is no control over who might be asked to make a decision about the article. This means the paper often ends up taking the form of a traditional ‘scientific’ paper reporting on empirical research, and using the IMRAD structure mentioned in my last blog. Even so, I can’t seem to keep the results and discussion separate in qualitative research! It just doesn’t seem to make sense in the kind of writing I do.

In contrast, book chapters in edited collections seem to be places where one can take rather more risks. Book chapters allow more space for reflection on bigger ideas than journal articles, and a little more licence to be more adventurous in the approach to the topic. Perhaps this is partly because, again in Education research, the essay form is more common in book chapters than in journal articles. As part of an edited collection, these chapters don’t need to stand alone in the way that articles usually do, even in special issues; rather, they sit alongside other chapters exploring closely related issues. This often allows for some cross referencing between chapters, either by authors or the editors, so that each chapter doesn’t need to say absolutely everything on the topic, and the ideas can expand out beyond the individual chapter. In this situation, a quite distinctive, personally inflected contribution can be valued for the facet that it adds to the composite whole. It also seems that those reviewing the chapter, the editors and possibly other contributors to the collection, are likely to be a more empathetic readership in terms of their interests and concerns. I’m not suggesting that this necessarily makes it an easier option, but it does feel less like writing into the black void of the unknown.

Pat Thomson makes a good case for the advantages of book chapters, but there is some debate about the usefulness of articles vs chapters in terms of citations and profiling (see Kent Anderson in ‘The Scholarly Kitchen’ and Deevybee in ‘BishopBlog’). While these arguments against book chapters may become less and less valid as e-books become more visible through standard search engines, doctoral candidates should at least be aware of these other elements in the equation. If they are thinking about a thesis by publication or publishing from a more traditional thesis format, concerns about building a research profile and becoming known in the field might play into these decisions.

What’s your experience of writing in these two contexts? Do you find that you write much the same, regardless of the type of publication, or do you find yourself modifying your approach? Is this because of the audience you anticipate for the different genres? And what advice should we offer doctoral candidates considering these options as part of a thesis by publication? All suggestions gratefully received!"

===============================================================================

An article is written by any person based on work carried out by him or his views on a specific subject whereas a chapter gives condensed/ collective information about by a person on the specific subject.

A chapter can be a part of a book or thesis or report and it constitutes only a part of the larger aspect of the subject, whereas an article in itself is sufficient discussion on the whole subject matter of interest. It is safe to say that an Article is our publication, for the presentation of our ideas & knowledge for our satisfaction & also for presenting the same to our readers or viewers.While presenting the publication in the form of book in order to maintain the continuity of our writings we present the same in the form of our chapter in our book.

The following was culled from a post by Bartomeus in 2013, titled:

Book chapters vs Journal papers.

I was offered to write a book chapter (a real one, not for a predatory editorial) and I asked my lab mate what she thought about it, given that time spent writing book chapters is time I am not writing papers in my queue. She kindly replied, but I already knew the answer because, all in all, we share office, we are both postdocs on the same research topic, and in general have a similar background. Then I asked my other virtual lab mates in tweeter and, as always, I got a very stimulating diversity of opinions, so here I post my take home message from the discussion.

Basically there are two opinions: One is “

Book chapters don’t get cited” (link via @berettfavaro, but others shared similar stories with recommendations of not to lose time there). However quite other people jump on defending that books are still well read. Finally some people gave his advice on what to write about:

So, I agree that books don’t get cited, but I also agree that (some) books get read. In fact, I read myself quite a lot of science books (Julie Lockwood

Avian Invasions is a great in deep book on a particular topic, or

Cognitive Ecology of pollinators, edited by Chitka and Thomson, is a terrific compendium of knowledge merging two amazing topics). However:

I don’t cite books.

So if you want to be cited do not write a book chapter. If what you have to say fits into a review or a research article, don’t write a book chapter. But if you have something to say for which papers are not the perfect fit (e.g. provide a historical overview of the topic, speculate about merging topics) then write a book chapter! It also will look nice in your CV.

Finally some people had a fair point on availability, a thing to take into account:

@ibartomeus I’ve done 3 this year and I’m concerned about future accessibility. In my field, books are getting expensive too, who buys them?

In summary:

- Book chapters are not papers.

- They won’t get cited, but will get read. However…

- Make sure your editorial is well-known (& also sells pdf versions /allow preprints in your web)

- For early career researchers one/two book chapters can give you credit, but remember that you will be evaluated mainly on papers, so keep the ratio of books/papers low.

PS: Yes, I will write it!

======================================================================

Basically, PhD researcher students have a choice of type of thesis. It is helpful to ask for the advice and help of your supervisor when initially writing for publication. According to James Hartley et al (2009), some readers might like to note that the essence here is that postgraduates like publishing before the thesis but that it can delay the production of it by about 6 months!

It is worth noting that like a lot of things in academia, I think this will heavily depend on what discipline you're in. In computer science for example, while there's nothing wrong with a book chapter, a paper at a conference or in a journal is typically more valuable.

The reason normally given is that papers are peer reviewed (as compared to edited), so they are somehow more 'valid'. Having said that, there's always myriad exceptions. Writing a whole book that everyone uses is much better than a few papers. Later in the career, book chapters perhaps gain value as they're a mark of respect and prestige (once you've already proven your research ability).

As a counter-point though, from my limited experience, it seems that book chapters are much more common in bioinformatics and operations research, and thus are viewed more highly.

Talk to fellow academics in your area, their opinion will be the best guide.

According to another respondent Jeff, "even within computer science, many book chapters are also formally refereed. It just depends on the book. Depending on your institution that you're at, if they take into account the world wide university rankings, then generally, Journal Articles will be of highest value out of all publication types."

see: shanghairanking.com/ARWU-Methodology-2016.html timeshighereducation.com/news/… topuniversities.com/subject-rankings/methodology (I Believe QS uses just Articles and Reviews, but I couldn't find that in that link. These are also the top 3 university rankings, so they do provide some context) – TMP4.

In my field a peer reviewed article counts for a lot more than a chapter in an edited book. That said, a published chapter in an edited book counts a lot more for job searches than a working/submitted/under review/under revision manuscript. Often edited books lead to a publication in press much quicker than a journal. I would definitely look into the time scale of the book chapter.

It may depend on the book. If the other chapters are being authored by big shots, then their prestige could rub off. On the other hand, if the other chapters are authored by less well-known people, then it might not be seen as that great. Another thing to consider: your university or department might weight impact factors in their assessment of your research quality, which means publishing in a good journal will be of the most benefit. In the end, the strength of the article itself will say a lot, independent of the publishing venue. If it becomes a classic in the field with lots of citations, then that's pretty good, no matter what.

It's based off the field but the general rule is to pump articles because they are peer reviewed. However, some publishers have a review process so if the chapter is in a handbook or in a collection that will be important to the field then you're good. Look at publisher rankings and try to only publish chapters under top ranked book publishers. If you're a junior tenure track then ask colleagues and dean for tenure and promotion info. I will say that in the humanities or social sciences you are more likely to have your chapter cited by another person in their work than an article. Hope some of this helps.

====================================================================

In Dorrothy Bishop's blog, "Inappropriate use of journal impact factors has been much in the spotlight. The impact factor is not only a poor indicator of research quality but it is also blamed for

delaying publication of good science, and even encouraging dishonesty. My own experience is in line with this: some of my most highly-cited work has appeared in relatively humble journals. In the age of the internet, there are three things that determine if a paper gets noticed: it needs to be tagged so that it will be found on a computer search, it needs to be accessible and not locked behind a paywall, and it needs to be well-written and interesting.

While I'm not a slave to metrics, I am, like all academics these days, fascinated by the citation data provided by sources such as Google Scholar, and pleased when I see that something I have written has been cited by others. The other side of the coin is the depression that ensues when I find that a paper into which I have distilled my deepest wisdom has been ignored by the world. Often, it's hard to say why one article is popular and another is not. The papers I'm proudest of tend to be those that required the greatest intellectual effort, but these are seldom the most cited. Typically, they are the more technical or mathematical articles; others find them as hard to read as I found them to write. Google Scholar reveals, however, one factor that exerts a massive impact on whether a paper is cited or not: whether it appears in a journal or an edited book.

I've had my suspicions about this for some time, and it has made me very reluctant to write book chapters. This can be difficult. Quite often, a chapter for the proceedings is the price one is expected to pay for an expenses-paid invitation to a conference. And many of my friends and colleagues get overtaken by enthusiasm for editing a book and are keen for me to write something. But statistical analysis of citation data confirms my misgivings.

Google Scholar is surprisingly coy in terms of what it allows you to download. It will show you citations of your papers on the screen, but I have not found a way to download these data. (I'm a recent convert to

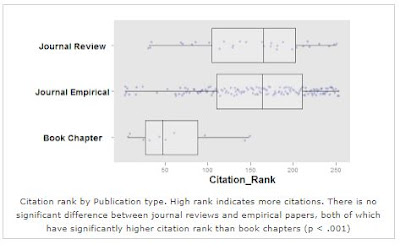

data-scraping in R, but you get a firm rap over the knuckles for improper behaviour if you attempt to use this approach to probe Google Scholar too closely). So in what follows I treated rank order of citations, rather than absolute citation level as my dependent variable. I downloaded a listing of my papers, ranked by citations, and coded them according to whether the article appeared in a journal or as a book chapter. Book chapters tend not to be empirical – they are more often review papers, or conceptual pieces - so to control for that I subdivided the journal articles into empirical and theoretical/review pieces. I also excluded papers published after 2007, to allow for the fact that recent papers haven't had a chance to get cited much, as well as any odd items such as book reviews. To make interpretation more intuitive, I inverted the rank order, so that a high score meant lots of citations, and the boxplots showing the results are in the Figure below.

Because I'm nerdy about these things, I did some stats, but you don't really need them. The trend is very clear in the boxplot: book chapters don't get cited. Well, you might say, maybe this is because they aren't so good; after all, book chapters aren't usually peer reviewed. It could be true, but I doubt it. My own appraisal is that these chapters contain some of my best writing, because they allowed me to think about broader theoretical issues and integrate ideas from different perspectives in a way that is not so easy in an empirical article. Perhaps, then, it's because these papers are theoretical that they aren't cited. But no: look at the non-empirical pieces published in journals. Their citation level is just as high as papers reporting empirical data. Could publication year play a part? As mentioned above, I excluded papers from the past five years; after doing this, there was no overall correlation between citation level and publication year.

Things may be different for other disciplines, especially in humanities, where publication in books is much more common. But if you publish in a field where most publications are in journals, then I suspect the trend I see in my own work will apply to you too. Quite simply, if you write a chapter for an edited book, you might as well write the paper and then bury it in a hole in the ground.

Accessibility is the problem. However good your chapter is, if readers don't have access to the book, they won't find it. In the past, there was at least a faint hope that they may happen upon the book in a library, but these days, most of us don't bother with any articles that we can't download from the internet.

I'm curious as to whether publishers have any plans to tackle this issue. Are they still producing edited collections? I still get asked to contribute to these from time to time, but perhaps not so often as in the past. An obvious solution would be to put edited books online, just like journals, but there would need to be a radical rethink of access costs if so. Nobody is going to want to pay $30 to download a single chapter. Maybe publishers could make book chapters freely available one or two years after publication - I see no purpose in locking this material away from the public, and it seems unlikely this would damage book sales. If publishers don't want to be responsible for putting material online, they could simply return copyright to authors, who would be free to do so.

My own solution would be for editors of such collections to take matters into their own hands, bypass publishers altogether, and produce freely downloadable, web-based copy. But until that happens, my advice to any academic who is tempted to write a chapter for an edited collection is don't."

==================================================================

In another post by Kent Anderson (2011), he told how he wrote a chapter for an upcoming book about academic and professional publishing. He had also written chapters in the past for other academic books about publishing. "Writing a chapter is always a worthwhile experience — I like to write, I like the topics I’m selected to tackle, and I like the editors. But even with the books in hand, these chapters also seem to disappear under the waves like anvils, never to be heard from again.

So, the books sit on shelves, mute testimony to a spate of writing, editing, and aspirations — seemingly unlikely to generate the impact, buzz, reputation, or knowledge transfer I’d once hoped."

"It seems I’m not alone" he said.

A recent blog post by Dorothy Bishop (a professor of developmental neuropsychology at Oxford, writing on her blog as Deevybee) explored how citations to academic book chapters fare in Google Scholar compared to citations to journal review articles and journal empirical (scientific) articles. While she expected a difference between scientific articles and book chapters, she was surprised to find a large difference between review articles and book chapters — after all, book chapters are akin to review articles, just published in a thematic book rather than a subject-area journal. Being competent with statistical software, she generated the following graph from her findings.

On average, book chapters generated about 1/3 of the citation rank of journal articles in her sample. Based on these relatively stark and grim findings, Bishop writes:

Quite simply, if you write a chapter for an edited book, you might as well write the paper and then bury it in a hole in the ground.

Why would this be? What factors would explain a lack of citations to book chapters, despite quality authors, interesting topics, important knowledge distillation, highly qualified editors, broad distribution, and prestigious publishers?

Bishop speculates that books suffer because they don’t have proper support from her three requirements for attention:

. . . there are three things that determine if a paper gets noticed: it needs to be tagged so that it will be found on a computer search, it needs to be accessible and not locked behind a paywall, and it needs to be well-written and interesting.

Bishop then notes that book chapters are often very well-written and interesting. She punts on the metadata issue, which I’ll return to. As for paywalls, we long ago worked out how to have everything discoverable behind paywalls. Nevertheless, for Bishop:

Accessibility is the problem. However good your chapter is, if readers don’t have access to the book, they won’t find it. In the past, there was at least a faint hope that they may happen upon the book in a library, but these days, most of us don’t bother with any articles that we can’t download from the internet.

I think this diagnosis of the relative obscurity of book chapters compared to journal articles comes up short in a number of ways, and with a poor diagnosis, the remedy won’t be quite right. Here are some other factors to consider:

Books aren’t as available online as journal articles because they are put into different packaging. Journals long ago moved into the “article economy,” shedding the volume/issue shell for searchable articles, in every way except citation construction and print delivery. Books remain in a packaging shell, with chapters trapped therein. There is no “chapter economy.” This limits book metadata and searchability to often the shell components and not the muscle and sinew — aka, the chapters.

Journals are broadcast on a regular basis, books are not. The common promotion of journal articles through email lists, print publication, aggregators, portals, journal clubs, and so forth creates much greater community awareness. Not only are the journal brands more predictable, constant, and “in your face,” the articles are anticipated on a weekly, bi-weekly, monthly, or quarterly basis.

Regular publication means bigger metadata footprints. Books come out sporadically, with a changing cast of characters — topics, editors, authors, titles, subjects. Journals are more predictable, with editors, editorial features, and topics that repeat themselves regularly, expanding and deepening the property’s metadata with every new issue.

New information supports awareness of companion content. The novelty contained in most scientific (empirical) articles draws media coverage for many journals and high interest from the most passionate researchers and practitioners in the field. This magnetic pull also draws these same influential sources of awareness-building into the review articles, increasing reader and community awareness of these.

Bishop has raised a very interesting question for book publishers in this era — how and why are you at such a disadvantage in citation systems? Her request for publishers to address these deficiencies is also spot-on. But her diagnosis of the problem comes us short — as done mine, I’m sure.

Some publishers have modified their books into robust online properties, with regular updates, email lists, and so forth — O’Reilly, McGraw-Hill, and others. Perhaps authors should become more selective, preferring these properties to bounded, sporadically published editions. After all, the impact difference that’s at stake may be sizable.

==============================================================

According to another contributor David; "it’s not a question of access, it’s a question of discoverability. Most researchers, through their libraries or their own funds, can gain access to a book. But they have to know that book exists. In medicine and the life sciences, if the full text of the article is not in Google or PubMed, it’s unlikely most will ever find it.

That’s why, years ago at CSHL Press, we converted several of our long-running book series into journals. CSH Protocols (

http://www.cshprotocols.org) was the first, given that when queried about where they found their laboratory methods, scientists almost always responded, “Google.” This has (since my departure) been followed by highly successful review journals, CSH Perspectives in Biology (

http://www.cshperspectives.org) and CSH Perspectives in Medicine (

http://perspectivesinmedicine.org/), both created from CSHL’s long-running monograph series. The content of these journals is still available in collected book form for those who prefer it that way.

There’s also a real benefit in this approach as it’s much, much easier to get authors to write an article for a PubMed-indexed, Impact Factor-having journal than it is to get them to write a book chapter. There seems, at least in these fields, to be greater career credit given for the journal article than a book contribution."

He added that: "From my experience, the prices are high simply because of economies of scale. A popular fiction/non-fiction book can cover costs with a low price because it’s expected to sell tens of thousands (if not hundreds of thousands) of copies. Most scholarly works are only going to appeal to a much smaller audience (and many can only be read by a tiny audience with the background knowledge to make the work comprehensible). If you’re only going to sell 500 copies of a book (and for some books, that may be a stretch), then you have to charge more per book to recover your costs.

Remember also that scholarly works have expenses that other types of books often don’t–fact checking, reference checking, licensing of figures and images for re-use from previous publishers, color printing, etc. Only the last of these costs goes away when you move to a digital format."

=============================================================

One would agree that the problem is “Discoverability” and electronic access. According to DEBORAH LENARES, "here is another reason why book publishers should make their content available to academic libraries as ebooks, AND supply the full text of the book content to the library discovery systems such as Summon. Students (and dare I say faculty) increasingly forgo materials they have to leave their seat to retrieve. If the chapter is discoverable in their library’s discovery system, and they can link to the chapter of interest immediately they are more likely to use the content."

Another contributor Sandy Thatcher, said: "David Wojick’s speculation may be true for edited books in science; it is not true for edited books in the humanities and social sciences, which are put through just as rigorous a review process as any single-authored book is. As part of this review, any seriously deficient chapter is likely to be dropped as a condition of publication.

Until very recently, book chapters were not assigned DOIs, as journal articles are. But increasingly they are, and this will help with discoverability. So too will the cross-searchability between book and journal content in such aggregations as the UPCC."

There are two fundamental weaknesses with Bishop’s citation comparison:

1) She assumes that the quality between format sources is equal — it is not (see: David W’s comment)

2) She assumes that Google is a reliable and valid source of citations. — it is not. This is apparent from the figure where empirical journal articles do as well statistically as review articles. This should have thrown up a red flag.

Access to a document an important antecedent to a citation, but there are more important factors at play (i.e. relevance, discoverability, and quality). Thankfully, self-selection and editorial selection tends to concentrate them all.

==================================================================

In another blog by Pat Thomson (2013), titled: I like writing book chapters. She said: "If you look at my publications – well I don’t mean you to do this literally – but IF you did, you’d see that I’ve written quite a lot of them. In the last month I’ve been sent two books which I’ve got chapters in, I’m expecting another collection as well as some chapter proofs any day – and I’m just starting on writing a chapter. So I really do think they’re OK.

The reason I like writing chapters is because they (generally) offer different opportunities for academic writing from the stock-in-trade journal article.

For a start, you can assume with a book chapter that you don’t have to convince readers that the topic you’re writing about is important. The editors are going to do that in the foreword. They are also likely to do a pretty thorough survey of the field, and to cover its history. So you don’t have to do that kind of literature work in a chapter, unless it is one about the literature ( see below). You just have to situate your own position and indicate the literatures that you draw on and to which you are talking/contributing.

And I reckon you can often be more creative as a writer in a chapter.

Not all book chapters are the same of course. There are different kinds of edited books which require different kinds of writing and different kinds of creaivity.

There are for example overtly pedagogical texts written for under- and post- graduate courses. The writing challenge here is quite different from a journal article – the reader is a learner, and the job of the chapter writer is to teach them about something. The writing must therefore be clear, engaging, the content well scaffolded; there may also be a need for examples, exercises and annotated bibliographies – perhaps even online links. It takes imagination and innovation in order to present instructional material so that it anticipates questions and answers them.

Then there are the chapters in international handbooks which set out to provide a state-of-the-art review of the field. The challenge here is not only to present a survey which identifies key debates, challenges and trends, but also to construct and argue for a future agenda – all the while not sending the reader to sleep with an excess of authors and titles and dates.

And there are topic based edited collections which aim to deliberately offer a variety of perspectives, to explore and to debate important questions. This is where the writer is most likely to be able to negotiate with the editor/s about a creative response. This is because topic-based edited collections often benefit from having variations as they keep readers moving through the text. So there is room for writerly manoeuvre. I have for example contributed chapters which are photo essays, multi-voiced accounts, auto-ethnographic words and images, heavily edited interview transcripts and variously structured narratives.

These kinds of chapters are the ones I most enjoy writing. It’s not that you can’t play with the journal structure, you can if you choose your journal carefully, and if you argue your case. But you generally don’t have to work so hard on this with the edited book. Provided the editor is up for some variation in the collection, you can think pretty creatively about how to present your material.

You can of course exercise the same kind of creativity in a whole book – but it is a much more challenging task. A book chapter is a good way in to alternative modes of academic writing. It’s a place where you can think and do much more about the WRITING aspect of academic writing. It’s a place to focus directly on the reader rather than primarily on the referees. It’s a place to practice and develop the craft of authoring.

So, that’s why I like writing book chapters….which I’m now about to get back to."

====================================================================

According to Bill Karsdorf, I think the most basic answer to this question is that most books are not in CrossRef and don’t have DOIs, especially not chapter-level DOIs. This is changing, and CrossRef is working on helping to change this, but the reality is that right now, especially outside of STM (and unfortunately often still within STM), book publishers just don’t think about this. They are fixated on _distribution_ (and the eCommerce and DRM issues associated with the selling of books) to the detriment of _citation_. I do a lot of work with book publishers (many or most of them scholarly or academic in nature) and you would be absolutely shocked at how often I hear the phrase “what’s a DOI?” I’m not kidding!!!

I firmly believe that the rapid transition from print to online for journal content was catalyzed by CrossRef, which provided the ability to cite and link to cited resources (at first overwhelmingly journal articles), which then in turn put pressure on publishers to make those resources available (under whatever commercial arrangements) online. Now if a journal article is not online and doesn’t have a DOI it’s virtually invisible; put another way, virtually all journal articles ARE available online, DO have DOIs, ARE in CrossRef. This has simply not yet happened in books, to a sufficient extent. But it’s about to. How can it not?

No more invisible book chapters, people!

==========================================================

The business model of books compared to journals also plays into this. With books it’s a one-off marketing push, before and around publication. Then maybe some cluster work in the next 6-12 months. Then move on to the next book.

There is also no incentive to promote usage of the book once it’s been bought. (Cynically, the reverse is true; if people forget they have the last book on this topic they might be the new one…)

With journals it’s a continuous push of articles to drive ‘usage’, to drive citations. To drive an impact factor.To drive resubscription.

With books it’s make the sale. Move on.

The business incentives are different. If the book impact factor ever gets off the ground then maybe this will change. Maybe PDA will drive some changes here as well. (Has Joe Esposito looked at this in his project?).

As Sandy Thatcher mentioned above, university presses and other scholarly publishers have recently gained the opportunity to start placing academic monographs and edited collections in aggregated collections such as Project Muse, JSTOR, and others, where chapters are now tagged for searchability. This is all very new, less than a year old. Also, generalizations about STM books and journals do not apply across the board to all disciplines, which do not all measure influence based on citations and impact factors. Consider whether a book, article, or chapter is used in classroom teaching, discussed in conference papers and panels that are never published as proceedings, or discussed at length in influential (non-journal) media like the London Review of Books, Times Higher Education Supplement, New York Review of Books, or Chronicle of Higher Education.

========================================================================

It depends on what your definition of a book is. Lots of researchers contribute chapters to http://www.annualreviews.org which are considered to be books by many libraries and individuals, but they are indexed as if they are journals in many databases. The Annual Reviews are highly respected publications with high IFs for the most part. So, what are they? Are they books or journals?

From the end-user side the meta-deta and format comments on this great post make the most sense. Like many people, I rely upon internet databases to do research. Academic edited volumes rarely have per chapter tagging. So, the book may not be tagged according to my interest or search because it is too broad. And there is no tagging for the chapter that would have been helpful. And, if I do find the chapter rarely can I read it online, even when using university library proxies. They simply don’t scan chapters that way. That means a trip to check the book out. While I do that frequently I can understand being in the field or working on a diss from afar and that being a roadblock. Finally, why aren’t academic volumes routinely in e-formats? And even when they are why are they so damned expensive?? $80 for an e-book is not uncommon in my experience. That’s for a chapter I’m not sure I need because I can’t read it beforehand, by the way.

======================================================================

CONCLUSION:

In my candid opinion and professional opinion, it is worth it. Currently, book chapters are more accessible and ebook chapters have DOI given to them so they can be downloaded and easily cited on research journal articles and review papers. Most contributors agree that it is good to do it but one must know that it may end up in a book shelf if not of high impact factor, notable editors, good academic publisher and of high value. SO, if you have an opportunity as a PhD researcher, a post-doctoral researcher or a researcher in academia, it is worth contributing to knowledge.

However, if it is an Encyclopaedia, it will be rated higher than Handbooks and normal Textbooks. So know the area you are writing the Book Chapter on, and make it citeable by citing some top journals too, so they can be cross-referenced. Book Chapters are sometimes based on business models, so they are economy-based. However, they are also good to help you express your view on a subject area. It should also be noted that they are also peer-reviewed.

Please, DO it, write the book chapter. The internet helps and students can also get the request to the library to obtain a copy. As an author, you get a copy of the book, and it can help if you add part of your PhD thesis in the work. However, seek advice from your supervisor and ask your colleagues for opinions. Make sure you concentrate more on research journals though than on book chapters. In academia, research journals have higher impact and citations than review papers, however, it depends on the institution of affiliation and the journal's impact factor.

References:

1.

Rene Tetzner(2005). Publishing research as book chapter: is it worthit. https://www.proof-reading-service.com/en/blog/publishing-research-as-book-chapters-is-it-worth-it/

2. Saunders, M.N., 2007. Research methods for business students, 5/e. Pearson Education India.

3. Bartomeus (2013).

Book chapters vs Journal papers. https://bartomeuslab.com/2013/11/11/book-chapters-vs-journal-papers/

4.

Cally Guerin(2014). Journal article or book chapters https://doctoralwriting.wordpress.com/2014/05/01/journal-article-or-book-chapter/

5. Hartley, J. & Betts, L. (2009). Publishing before the thesis: 58 postgraduate views. Higher Education Review, 411, 3, 29-44.

6. Sam Illingworth and Grant Allen (2016). Effective Science Communication. A practical guide to surviving as a scientist. Chapter 2- Publishing work in academic journals.

IOP Publishing Ltd.

Pages 2-17. http://iopscience.iop.org/book/978-0-7503-1170-0/chapter/bk978-0-7503-1170-0ch2

7. Lindy Woodrow (2014). Writing about Quantitative Research in Applied Linguistics. Chapter 14-Publishing Research: Book Chapters and Books. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1057%2F9780230369955_14.pdf

8. Kent Anderson (2011). Bury Your Writing — Why Do Academic Book Chapters Fail to Generate Citations? https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2012/08/28/bury-your-writing-why-do-academic-book-chapters-fail-to-generate-citations/

9. Dorothy Bishop (2012). How to bury your academic writing.

http://deevybee.blogspot.com/2012/08/how-to-bury-your-academic-writing.html

10. Pat Thomson (2013). why write book chapters. https://patthomson.net/2013/06/17/on-writing-book-chapters/

11. Eve Mardera, Helmut Kettenmann, & Sten Grillner (2010). Impacting our young. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1016516107

12. https://academia.stackexchange.com/questions/6133/how-does-a-book-chapter-in-an-edited-volume-compare-to-a-peer-reviewed-paper

13. https://www.researchgate.net/post/What_is_the_difference_between_an_article_and_a_chapter

Postcoital dysphoria (“post-sex blues”) or Postcoital depression (PCD):

Postcoital dysphoria (“post-sex blues”) or Postcoital depression (PCD): She explained that it comes down the explosion of hormones in the body after sex, including endorphins, oxytocin and prolactin.

She explained that it comes down the explosion of hormones in the body after sex, including endorphins, oxytocin and prolactin.